How miserable do you feel?

Updated | Misery Index updated for 2025 data

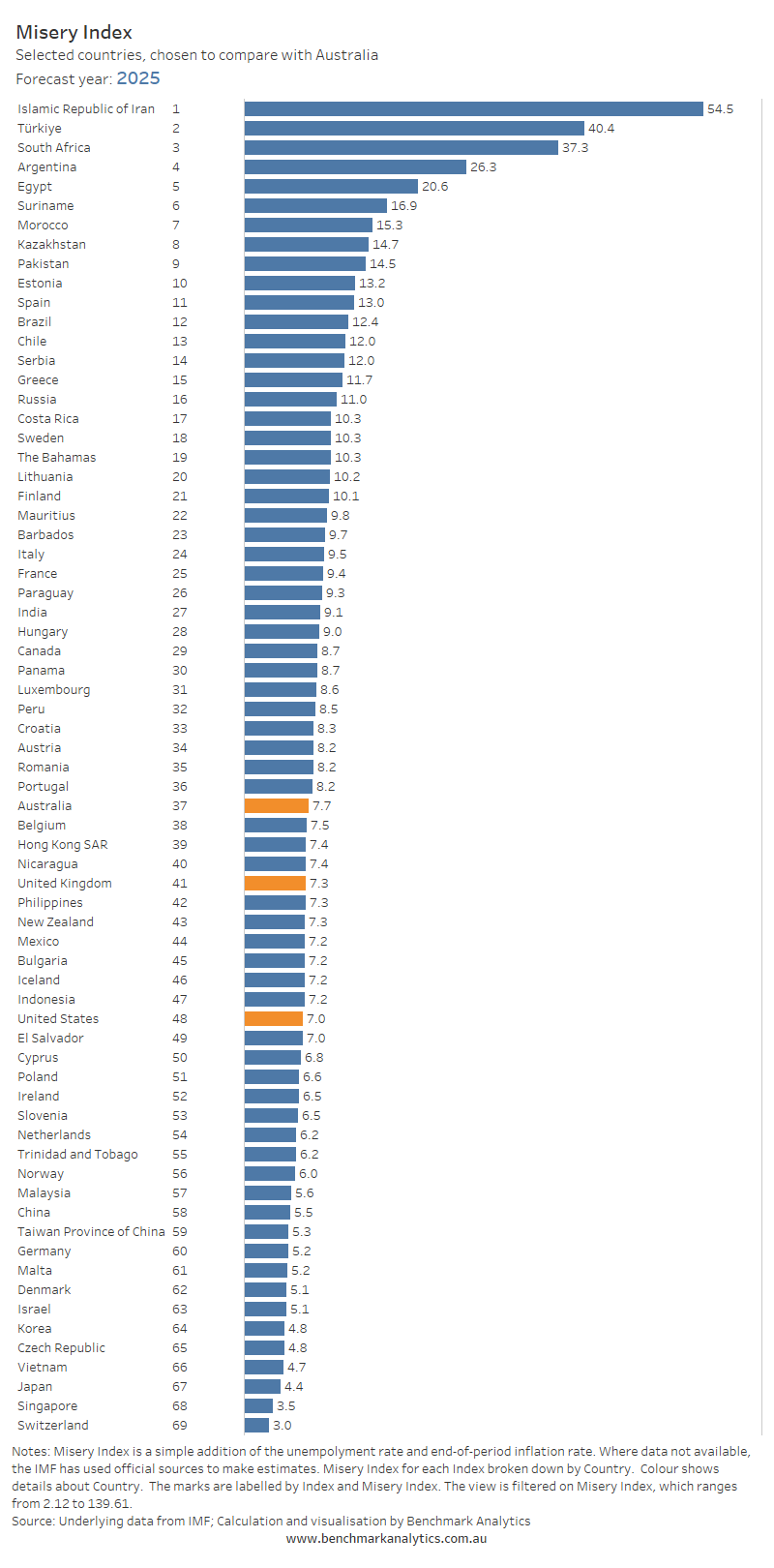

A commonly used and straightforward measure of a country's relative economic pain is known as the Misery Index. It involves a simple calculation: the addition of a country's unemployment rate and its inflation rate. Both indicators are undesirable—so the higher the total, the greater the presumed economic “misery” for a country’s citizens.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) publishes relatively high-quality, comparable data on unemployment and inflation across countries, allowing for a consistent comparison of Misery Index scores.

According to my calculations, among countries to which it makes sense to compare Australia, the most miserable is Iran, followed by Turkey and South Africa.

As of 2025, Iran scores a Misery Index of 54.5; Turkey, 40.5; and South Africa, 37.3.

Anecdotally, this aligns with broader realities. Iran has recently seen its proxy forces—Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis—largely dismantled by US and Israeli forces. South Africa is undergoing land confiscations from white farmers, some of whom are reportedly being granted asylum in the United States. While the Misery Index is purely an economic construct, it often reflects the deeper political and social turmoil of a country. Perhaps the two are more closely linked than the formula implies.

At the other end of the scale, we find the least miserable countries—and these results are intuitively satisfying as well. Switzerland leads with a Misery Index of just 3.0, followed by Singapore at 3.5 and Japan at 4.4. These nations are well known for their high living standards, stable economies, and relatively harmonious societies.

Australia’s performance is middling. We rank 37th out of a pool of 69 countries, with a score of 7.7. Notably, we’re edged out by both the United States (7.0) and the United Kingdom (7.3).

How miserable do you feel?

Tomorrow, I’ll post forecasts of global economic misery for the year 2030—based on projected unemployment and inflation rates from credible economic sources..

Backgrounder to the Misery Index from Chat GPT:

The Misery Index is a simple yet strikingly evocative economic indicator that captures the human cost of poor macroeconomic management. At its core, it combines two critical variables that affect the average citizen’s quality of life: the unemployment rate and the inflation rate. The higher the index, the greater the economic “misery” being felt by the public—through joblessness and rising living costs. Unlike more abstract economic metrics, the Misery Index resonates because it distils economic stress into an easy-to-grasp figure.

The term and original formulation of the Misery Index are credited to American economist Arthur Okun, a senior adviser to President Lyndon B. Johnson during the 1960s. Okun devised the index as a tool for understanding how economic conditions might influence public sentiment. While its construction is arithmetically straightforward—simply adding the unemployment and inflation rates—its policy implications are weighty. It encapsulates the trade-offs central banks and governments often face: stimulate growth and risk inflation, or suppress inflation and risk job losses.

The Misery Index gained real political prominence in the 1970s, particularly during the presidency of Jimmy Carter. At that time, the U.S. economy was beset by the rare and toxic combination of high inflation and high unemployment—a phenomenon later termed “stagflation.” The Misery Index soared, giving ammunition to political opponents and leading to its broader popularisation. Ronald Reagan famously used it during his 1980 campaign, quipping that “by this economic measure, things are twice as bad as they were four years ago.” The index had thus evolved from a niche academic concept to a potent political weapon.

Over time, several economists have proposed modifications to the original index to make it more reflective of contemporary economic concerns. One notable variant is the “Barro Misery Index,” named after Harvard economist Robert Barro. This version incorporates not just inflation and unemployment, but also long-term interest rates and GDP growth—penalising low growth and high borrowing costs. Barro’s goal was to create a more comprehensive picture of economic well-being, reflecting the fact that slow growth and tight credit can be as painful as joblessness or inflation.

Another modification comes from Steve Hanke, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, who has compiled a “World Misery Index” ranking countries by a modified score that includes inflation, unemployment, interest rates, and economic growth. Hanke’s work is especially notable for applying the concept globally, providing comparative misery scores across developing and developed economies alike. In countries like Venezuela or Zimbabwe, hyperinflation alone has often been sufficient to push the index into the stratosphere, highlighting just how destructive runaway prices can be to economic stability.

Critics of the Misery Index argue that its simplicity is both a strength and a weakness. It assumes equal weight between inflation and unemployment, even though their psychological and economic impacts can differ greatly depending on context. Moreover, the headline inflation rate does not always reflect cost-of-living pressures faced by lower-income households, just as the headline unemployment rate may mask underemployment or discouraged workers. Nevertheless, the index retains heuristic power—especially in public debate and media commentary—because of its ease of interpretation.

In today’s economic climate, where inflation has returned to the forefront after decades of dormancy and labour markets remain in flux due to post-pandemic shifts, the Misery Index is undergoing something of a renaissance. Policymakers face renewed pressure to balance price stability with employment support, and the Misery Index offers a blunt but effective barometer of public sentiment. When people feel squeezed at the supermarket and insecure in their jobs, their misery tends to be captured—however imperfectly—by a rising index score.

Ultimately, the enduring appeal of the Misery Index lies in its synthesis of macroeconomic outcomes with everyday experiences. While GDP growth or bond yield curves may better forecast market trends, the Misery Index speaks to something more fundamental: how difficult it feels to get by. In this sense, it remains a valuable, if imprecise, indicator of economic legitimacy and political accountability.