"He Cuts, You Pay" - Explained

A post helping to explain the Australian election

The Labor Party’s primary election catchphrase was “He Cuts, You Pay.” The “He” is obviously Peter Dutton, and the campaigners gathered evidence from the past where Dutton had attempted to trim government spending.

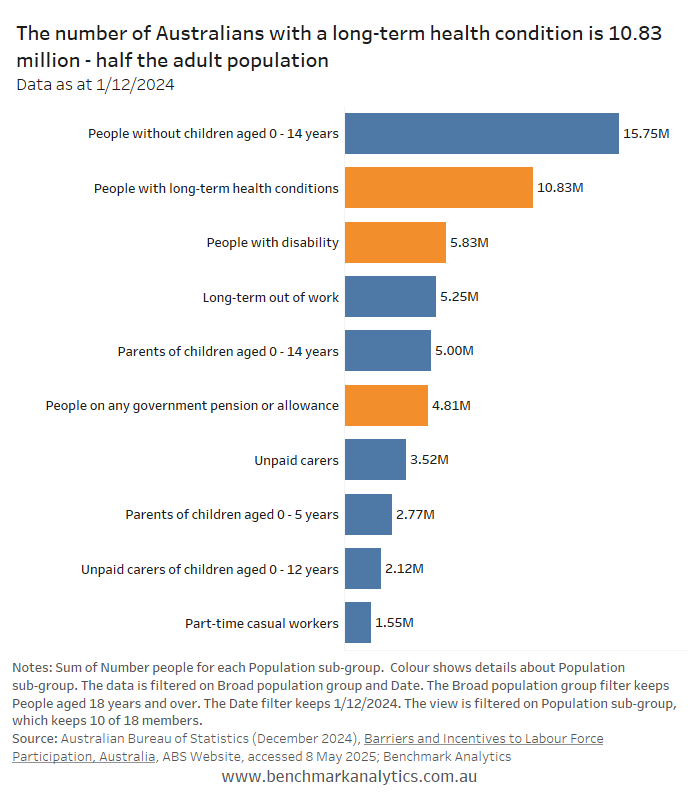

The potency of Labor’s message becomes clear when considering the size of demographic groups threatened by the prospect of government spending cuts, especially in the health sector. Labor’s fear campaign about health spending cuts under Dutton was aimed at an extraordinarily large demographic group.

Just about everyone uses a GP regularly, but there is also a very large pool of people who use the health system intensely. ABS data shows that more than ten million Australians consider themselves to have a long-term health condition, suggesting they believe they will require health care and medication for the rest of their lives.

Almost six million people report that they have a defined disability. This explains why Labor alleged the Coalition would cut the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

Almost five million Australians receive some form of government pension or allowance. Once again, the “He’ll Cut” message resonates strongly with this group.

See chart below. For a full breakdown of key demographic groups, please contact me directly. (Note these groups are not mutually exclusive, many people will classify into multiple categories.)

Spectator Article

For further election result analysis, please refer to my Spectator article published on 7 May. Here is a link to the magazine. The full article is also included below:

What did the election result say about Australia?

Nick Hossack

7 May 2025

There was one small incident during the Voice Referendum that I never understood, and it has stayed with me. Standing in the cardboard partition to cast my vote, I inadvertently saw the choices of the women on either side of me.

Both voted ‘No’. Nothing strange about that – 60 per cent of the electorate did the same. What was slightly unusual was their demographic profile. One was an Asian woman, probably in her early twenties, who had on a uni-style backpack and was fumbling around with an oversized, colourful water bottle. On the other side was a woman wearing a hijab and denim jeans.

Throughout the campaign, I had assumed the vote would split along left–right lines, with young people like these voting ‘Yes’, and all the oldies on the other side. I found these two ‘No’ voters very curious.

Later that night, the political right celebrated. There was relief that finally there had been some pushback against insane Wokeism. Celebrations continued for several weeks.

A question we should now ask is whether the Voice result diagnosis was correct. Was the vote really reflective of an underlying deep well of anti-Wokeism – was the big dog finally stirred? Or was something else going on?

Another interpretation may be that it was simply about money and handout culture. For 97 per cent of people, the Voice offered no direct benefit. Nothing.

In all aspects of life, taking an action for change involves a cost-benefit calculation: will this benefit me?

Normally, when it comes to political votes, political parties present a package of initiatives, some of those will benefit you and some won’t. There are costs and benefits.

The Voice proposal offered no direct benefits to roughly 97 per cent of the population.

So, by definition, if there was zero benefit for most people, then even the slightest perceived risk (cost) involved in voting ‘Yes’, it will lead you towards voting ‘No’.

The recent Labor election slogan, ‘He cuts, you pay!’ is just saying that Dutton represents higher costs and less benefit. My guess is that this hip-pocket idea is better at explaining the decisive Voice referendum result than that of anti-Wokeism.

A second point I’ve been considering post-election is something we used to talk about quite a bit when I worked as a political staffer – some decades ago now. We used to debate whether political parties, either state or federal, once consigned to opposition, should adopt one-term or two-term strategies.

The one-term strategy entails presenting a set of policies sufficiently broad to have a chance of winning the very next election. The two-term strategy involves recognising that a newly elected Australian government is likely to secure at least two terms, and so you may as well build a solid platform to offer voters when they start to want change.

A two-term strategy is akin to laying a concrete foundation for a house: shoring up the base and gradually pulling in new constituencies in an authentic way, through hard policy work and long-term community integration with good candidates.

Dutton seems to have chosen a one-term strategy. Putting aside the matter of the campaign’s execution, it’s hard to criticise Dutton for this choice. Polls suggested it was possible. While it ultimately proved unsuccessful, the indicators pointed to it being a valid choice – including deep resentment over cost-of-living pressures that were immediate and widespread.

However, as we used to debate, the cost of a one-term strategy is that if it fails, then it’s likely to put you out for three terms because the rebuilding is delayed by one year.

Third: one issue barely mentioned or acknowledged by the right is the state of the labour market. We must concede that while higher prices are making a mess of disposable income, there is a lot of income out there.

Albanese, in fact, has an impressive record in overseeing low unemployment – especially given the Reserve Bank has raised the cash rate by more than three percentage points since he was elected.

It pains me somewhat, but of all our Prime Ministers since 1978, Australia’s unemployment rate has averaged lowest under Albo.

This has provided the electorate with a level of comfort: at least workers can continue earning the money needed to pay for higher-cost goods. There appears to be little job insecurity – at least in those jobs not directly threatened by Artificial Intelligence.

Bank data on mortgage defaults of households, those most impacted by RBA rate increases, suggests the much-claimed household financial ‘pain’ and ‘doing it tough’ may be overstated and not as politically potent as claimed.

A fourth point – one likely to emerge soon – is whether there’s any benefit in the Coalition remaining intact this term. Why not split?

Let the Liberal Party chase the Teal and inner-city seats, and let the National Party lead, unrestrained, against Net Zero insanity.

The Nats could then rally the conservative base into a single force – perhaps forming some kind of alliance with One Nation and consolidating other disparate voices. This won’t happen with the Libs in their corner.

Without the constraint of the Liberals, the Nats could aggressively advocate proper energy policies, including reinvestment in coal and a move towards nuclear.

By freeing the Liberals from the Nats, they could position themselves to be ready when Albanese inevitably taps the people in the Teal and other wealthy suburbs to pay for his election promises and fund any further ‘reform’ agendas.

Because the Teals have marketed themselves as morally pristine and obsessed with ‘fairness’, they will find it impossible to energise themselves against what we know is coming: a host of taxation policies that will hit the wealthy suburbs in one way or another. This will probably include a land tax at some point which, depending on design, will essentially be paid by those living in the wealthier areas.

The Liberals need to be ready to move into that space – but they won’t be able to do so if there is ambiguity over Net Zero.

In time, the two parties may find a set of policies to form a coalition again – such as the elimination of tax bracket creep – but that won’t be needed for years.

The Net Zero schism will likely be settled by then, one way or another. In the meantime, they can rebuild and expand their bases with more agility and clarity.

A split may cause some problems at the state level, but moving apart at the national level is worth considering.

On the issue of women voters, I think this really is a crisis for the Coalition. I asked an early-twenties girl I saw yesterday whether she was glad the Labor Party had won the election. She paused, thought about it, and said, ‘I’m glad the Coalition lost!’ Ouch.

The complexity of the problem can best be illustrated by the strange commentary we are seeing that the Liberals need to embrace a female leader to win back women voters.

I wonder if Adam Bandt and Anthony Albanese are implicitly offended by such arguments. Why are the commentators urging a female leader but not acknowledging the obvious: the most successful Labor election ever was won with a male leader and male deputy.

But here is the complexity. Their intuition is correct. Albanese and Bandt are ultra-beta males. I’ve not followed Bandt much, but Albanese seems to mood-swing between instinctive severe nastiness when discussing Peter Dutton or Angus Taylor, to a quivering lip and holding back tears every time an audience claps him. This emotional turmoil doesn’t indicate he’s flush with testosterone.

Women voters, particularly alpha women like the Teals, are very comfortable with beta males in leadership positions. They don’t instinctively respect them, but beta males empower women through their own organic subordination.

I suspect the best way forward for the Libs is to forget trying to identify women as a project to be fixed, or to elect a leader with the aim of attracting women, and instead just focus on electing a leader who can best argue for policies that benefit everyone, men and women. Renewed focus on policy will be respected by everyone and the best way to increase the female vote.